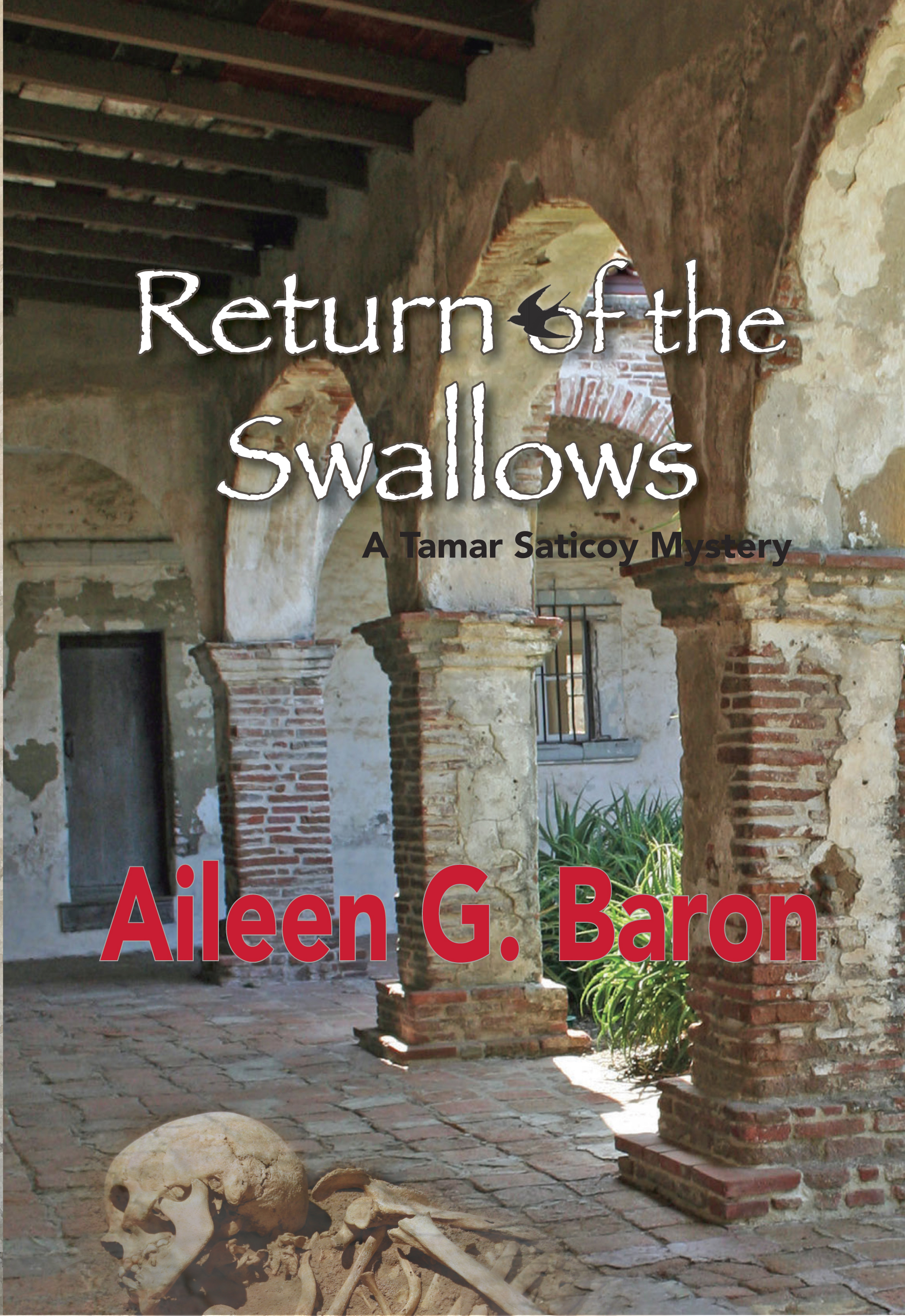

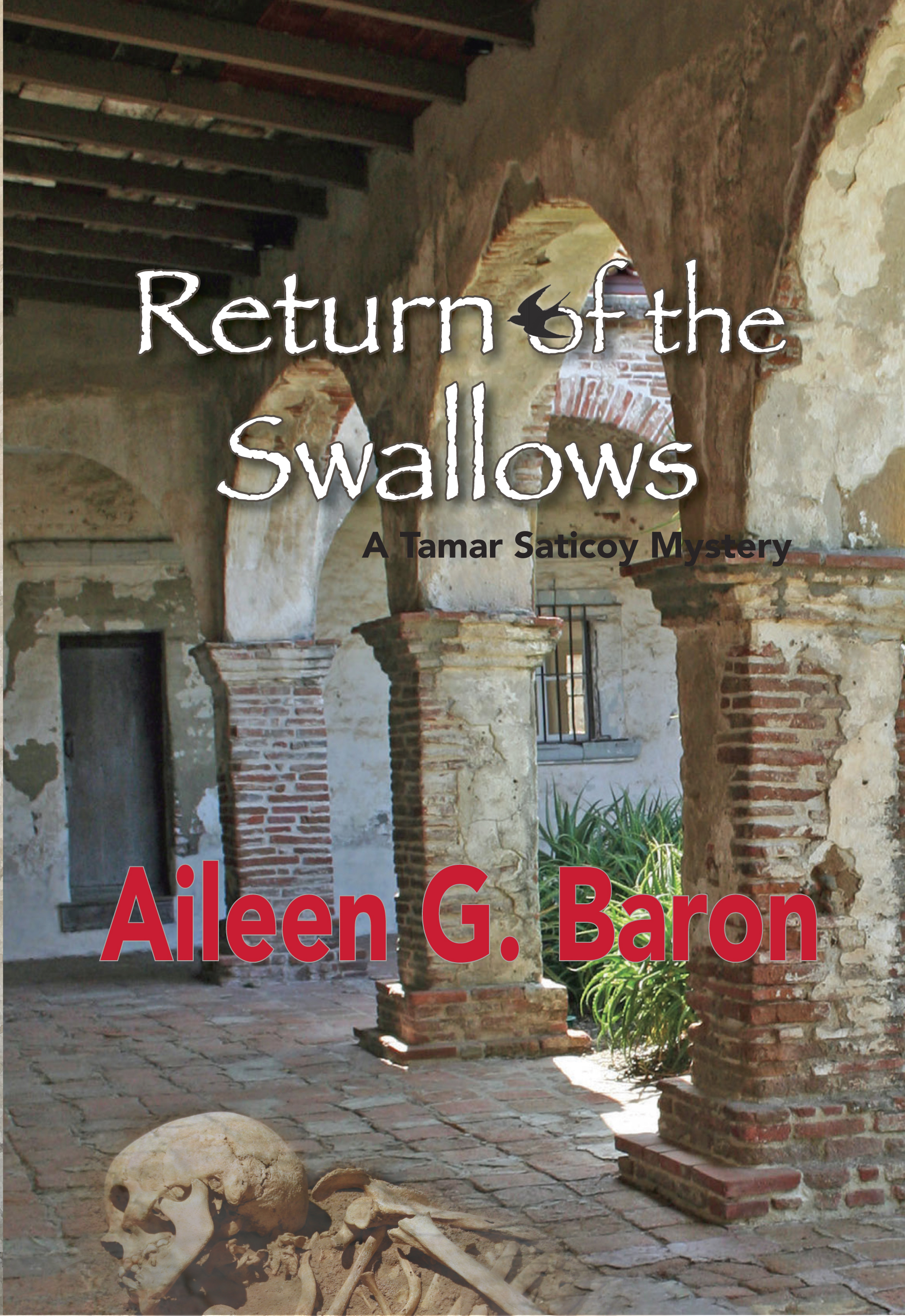

Excerpt from

Return of the Swallowsby Aileen G. Baron

Chapter One

Thailand

At Ban Boh Rahr on the Khorat Plateau, riches appear at the end of the rainy season, seeming to rise out of the ground.

On the road to Ban Boh Rahr from Bangkok, the Mercedes, gaudy with gold paint, bogged down in the mud and the man from Bangkok cursed.

He sat in the car, murmured jai yen nah, jai yen-yen, over and over, to cool his heart. He covered his shoes with plastic bags and got out to retrieve the wooden boards from the trunk, all the while mumbling the incantation the spirit doctor had given him for just such an occasion. The chant made no sense to him. It was in old Khmer, just nonsense syllables in his ears, but he didn’t care. It worked every time. He jammed the boards under the tires, got back into the car, threw away the plastic bags, snapped open his knife to scrape off the excess mud, put away the knife, and drove off.

It was November. The monsoons were over, and the man from Bangkok knew that at Ban Boh Rahr, treasures had eroded out of the ground and awaited him--painted pottery from the tombs and scattered bones festooned with bangles--washed out in the rains.

In the barren Northeast District, good only for rice, rivers had turned to mud. He passed rice paddies and quiet villages with spirit houses where the town’s guardian spirits lived, reached the Khorat Plateau where trees were scarce, and drove on to Ban Boh Rahr.

Tonight, Ban Boh Rahr would be empty. The villagers would all be at the Mekong. Tonight was the full moon. Tonight on the Mekong, the River Dragon, Naga, would greet the Lord Buddha, and the river would glow in flame.

The man from Bangkok reached Ban Boh Rahr, parked the Mercedes and climbed up to the site that rose above the fields surrounding the village, clutching at roots for a handhold, sliding back and climbing again to the top. From there, he watched the villagers skitter along the paths to the banks of the river to stare in awe as they saw Naga blaze.

In the distance, across the Mekong, lay the green uplands of the rainforests of Laos.

Tonight, Ban Boh Rahr was his for the taking.

He picked up the arm bones of a child, the brittle wrist bound by a stack of tiny bangles, and felt a chill. There’s no merit in this, stealing from the dead. The spirits will come after you in the night, take back the bones, and rob your soul.

Not here. Not here. There were no more spirits in Ban Boh Rahr. The farang took care of that, before they took away the trees and turned the red earth angry with fire. But the farang had made his mother rich in those days, when she was young and beautiful.

Money is powerful. Money is the soul of control. Money is reputation. And reputation is all.

The Lord Buddha said that all is illusion, that only the internal world is real.

The man from Bangkok cleared as much as he could from the surface of the site, then jumped into the pits dug by farang archaeologists. The sides of the pits, once straight and square were now soft and slumped by the rains. Just in case spirits were watching, he took off his shirt and turned it inside out to confuse them, before he put it back on.

He found material that had washed out in the rains on the bottom of the pits--bracelets and beads, spindle whorls and figurines, ladles and bowls, spearheads and axes--a plethora of bronze. He bagged it all to sell to the farang, so rich and dissolute, and to the Japanese hurrying through their one-week tours with their cameras and quick little steps. Japanese will buy anything. So will farang. They buy pieces of glass and think they are rubies.

The farang feel special and daring, because they think they are smuggling out the treasures of Thailand. But this is different. This is art, for collectors. This is a piece of ancient Thai history. Even if it was made yesterday, it is still a piece of history.

He picked up some sherds of painted pottery. Tomorrow, he would return and give these broken ceramic bits to peasants from the next village to make new pots that the archaeologist’s tests would mistake for ancient ones. He would buy the new pottery that the peasants had made since his last visit to sell to the farang.

The last time he was at that village, a fool peasant sold a black Hoabhinian pot to a farang. The peasant told the farang that it was an ancient monk’s bowl. He had to explain to the peasant that when the farang gets back to Bangkok, someone will tell him that the Hoabhinian period took place long before the Lord Buddha was born. There were no monks then, and the farang will know that he was cheated. That’s bad for business.

The peasant had put his hands together for a wai, raised them to his head and made a deep bow. The man from Bangkok answered the peasant with a perfunctory nod and half a smile.

Tomorrow, the man from Bangkok decided, he will seek out the peasant, and remind him gently, smiling, smiling all the while, that the black bowls were in use many centuries before the Lord Buddha was born. He will smile because Thailand is the land of smiles, but it will hurt his heart to smile to such a fool. He will show the villager his knife, use the knife to clean his fingernails, tell the fool that if it happens again, he will take care of things, he will make sure that the villager will never make or sell another bowl. And then, he thought, I will smile for real, and I will snap the knife closed.

The man from Bangkok filled large plastic bags, the kind they use for garbage, one after another, until he filled the trunk and the back seat of his gilt Mercedes.

Now the Mercedes held the magic of Thailand’s history, bagged and looted and almost ready for sale, and he started back to Bangkok.

Chapter Two

San Juan Capistrano, California

Tamar Saticoy sat back on her heels, took a deep breath and put down her trowel. Her knees ached, her shoulders were sore, her arms were tired. She had been clearing the tumble of burnt mud brick behind the ruin of the Great Stone Church at San Juan Capistrano Mission since early morning, taking turns with Mario, who was working the rocker screen.

Digging the collapsed wall charred in a fire, now calcined and hard, took longer than she had expected. She thought it would take less than a week when Sue Evans, the new historian at the Mission had called her to work on the restoration.

Tamar should have finished the wall two days ago, before St. Joseph’s Day. But now, crowds of visitors pressed around the jerrybuilt barrier of sawhorses.

Tamar usually worked in secluded areas, but today, she felt the crowds pressing on her, and felt irritated enough to say to Mario, “Surely these people have somewhere else to go.”

“It’s the day the swallows come back to Capistrano.” Mario answered in his soft Native American voice. “March 19.”

“Should have fenced off the area,” she said halfheartedly, and looked around.

Hummingbirds hovered over the roses, blackbirds splashed in the fountain in the central courtyard, crows flapped and cawed overhead, and scores of white pigeons waddled at the edge of the lily pond, pecked at the ground, and fluttered around clusters of visitors.

“Most of the birds are pigeons,” Mario said. “And crows”.

Tamar had convinced Mario to be the Native American observer mandated by Sacramento to monitor all archaeological excavations. Otherwise, she knew, the pseudo-Indian, Roy Geraldo, who had appointed himself titular head of the Juaneño, would demand to watch her dig at a hundred and fifty dollars a day for sitting in a chair under an umbrella with his arms folded across his chest.

Mario Portola was Tamar’s graduate student at Cal State, and a Capistrano elder. When the good Franciscan fathers came to California, they rounded up the local Indians for God and country. They named the tribe for the Mission, Capistrano or Juaneño, even though the Indians called themselves Acjachemen. The good fathers taught the Indians the arts of civilization and kept them in conditions of virtual slavery, men separated from women, and saved their souls by working them ten or twelve hours a day farming the Mission’s fields, constructing and repairing the Mission’s buildings. Somehow, Mario’s ancestors had survived and prospered.

Mario had been a high school math teacher, and later Superintendent of Schools. His wife, Katie, was the Educational Curator at Casa del Sol, the County Museum in Anaheim. He lived in a great, rambling Mission Revival house that he had inherited, perched on a bluff overlooking the sea. He also had a condo in Mammoth because he liked to ski, and a condo on Catalina, because he liked to sail. He returned to school to study archaeology when he retired so that he could excavate and restore his great-grandfather’s adobe.

No one could say, “Lo, the poor Indian,” about Mario, Tamar reflected.

She sighed and went back to work, loosening clumps of red-baked brick, mottled with clouds of black and gray. She set aside bricks too burnt and heavy for screening, while Mario saved bits of charcoal from the screen, wrapped them in aluminum foil, and labeled them for Radiocarbon dating.

She worked smoothly, moving the loosened bricks to the screen for Mario to sift through, each motion automatic from long habit. While she worked, she thought of all lost things--of the swallows that hadn’t arrived, of scourged spirits of dead Juaneños wafting over the gardens and the lily pond, their ghosts as white as the pigeons who fluttered through the Mission grounds.

And of Alex, and that long night in Mérida in the Yucatan when he never returned, the night she waited for him to celebrate--a double celebration for their first anniversary, and for Alex’s discovery of the lost site of Katamul hidden in the jungle.

A discordant clang from the cracked bells in the campanario broke into Tamar’s reverie. She thought for a moment of the mythical lost Mission bells that old wives’ tales said were buried somewhere under Mission Viejo.

Tamar glanced up and saw Sue Evans speaking rapidly to a gangly youth about fifteen years old as she escorted him toward the exit.

“What’s going on?” Tamar asked.

“According to legend, the bells ring by themselves to announce a disaster,” Mario said. “They rang before the earthquake that destroyed the Great Stone Church.”

“And this time?”

“That boy pulled at a bell.”

Tamar rocked back on her heels, and let her hands fall to her side, still clutching her trowel. She took a deep breath, unwound only for a few moments. No time for disaster. Time to get back to work. The marine layer that hovered over the Mission was burning off now, and the day was beginning to heat up.

Still, when someone shouted, “There’s one, there’s one,” she stopped to look up.

The visitors stood in groups, watching the sky. Sue Evans, pleasant and plump and dressed as a duenna from early California Mission days, moved among them with a platter of fried cactus leaves.

One man pointed at a crow flying overhead. Standing just beyond him, Roy Geraldo leaned against the ruined wall of the Old Stone Church and watched Tamar with dark eyes as hard and cold as the blade of a dagger, and she felt a chill.

He’s trouble.

She tried to ignore him, tried to ease the tension she felt when she saw him. She rotated her shoulders, rubbed the back of her neck, continued working on the tumble of burnt rubble, and jabbed the hardened bricks with the edge of her trowel, tossing loosened dirt into the screen.

Mario broke up the clumps and rocked the screen back and forth, sifting dirt to retrieve bits and pieces she might have missed: a piece broken off an eccentric crescent-shaped artifact that looked like a bear, a chiton shell, an otolith from the inner ear of a fish—all had been embedded in the clay of the mud brick.

Long ago, before they were imprisoned in the Mission, the Juaneño had lived off the sea.

Mario picked a small object from the screen, held it carefully between his thumb and forefinger, and brought it to Tamar.

“What is it?” he asked and handed it to her. “Ceramic? Part of a figurine?”

Tamar examined it under the magnifying glass hung from a cord around her neck.

“It’s a human toe bone.” She held her breath. “A charred phalanx.”

She cleaned the bone carefully with the camel’s hair brush from her pocket, and looked up to see Geraldo, stony and relentless, watching her.

“Someone’s buried beneath those bricks,” she told Mario, with a quiver of apprehension.

-- READ THE REVIEWS --

|